A Mysterious Land-Grab

When you’re driving through the United States’ vast and scenic patchwork of farmland, tech moguls may not immediately spring to mind. And so you may be surprised to learn that the person who owns more of our country’s fertile, picturesque landscape than anyone else is none other than Microsoft co-founder Bill Gates.

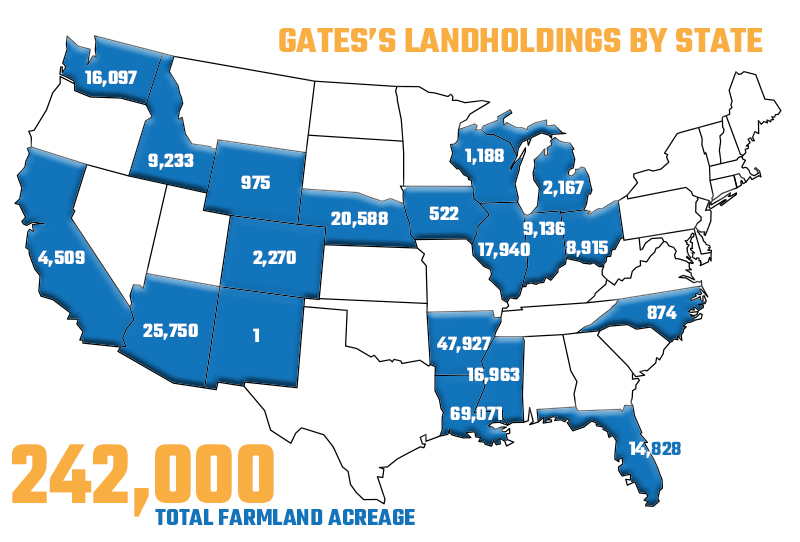

The speed, size, and secrecy of “Farmer Bill’s” land purchases (many of which were made using shell companies) set off alarm bells for many people. Why does a tech-obsessed billionaire need more than 240,000 acres of farmland (that we know about), and what is he going to do with it all?

Gates himself claims the land is just a good, solid investment, but many, including U.S. Representative Dusty Johnson, are calling for an explanation.

Source: Land Report

Just Who Are We Dealing with, Anyway?

Until Bill coughs up that explanation, we can start by looking at established facts to learn about the values and intentions of the United States’ largest private farmland owner.

Thanks to his book, How to Avoid a Climate Disaster, we know that Gates is very concerned about the impacts of severe weather on our food system. We also know that, in addition to that chunk of U.S. farmland about the size of Hong Kong, Gates has investments across our food and farm system, including in John Deere and Beyond Meat. From these facts, we could conclude that Gates suspects our food supply is going to be limited, and is ensuring he will profit from its production — a potentially benign and even smart business decision.

Another demonstrable fact is that Gates financially supports technological solutions to problems. The portfolio for Breakthrough Energy Ventures — where he chairs a board with other billionaires like Jeff Bezos and Elon Musk — includes Pivot Bio, focused on in-field nitrogen fixation; plant-based ingredients producer Motif Foodworks; and Pachama, which collects and analyzes carbon sequestration data from forests. Gates also just launched Cropin Cloud, an integrated app that aims to “digitize” farming operations by collecting farmers’ data. It claims to have the biggest crop knowledge graph, with more than 500 crops and 10,000 crop varieties. Following the money, it’s clear that Gates prioritizes technological solutions over farmers’ innovations.

We can’t safely conclude too much beyond this, because Bill Gates has only just begun to insert himself into the mechanisms of the U.S. food system. To find out what he might do if he is ever fully at the reins, we need to zoom out to a global perspective, and take a hard look at what he has done to food systems elsewhere.

Bill Gates: Seed Pirate, Agricultural Invader

The story of Bill Gates’s global conquests involve a number of interconnected organizations, all funded or controlled by Gates or his foundation and acting out his will. Below is just a sample:

Founded back in 1971 as part of the controversial “Green Revolution,” CGIAR is a massive research institute that boasts the world’s largest gene banks, managing more than 750,000 seeds acquired from farmers. CGIAR encourages agricultural mechanization and advances in crop breeding — and consistently transfers its research and seeds from scientific research institutions to for-profit corporations.

Gates has poured hundreds of millions into CGIAR, and now exerts massive influence over its operations: At Gates’s urging, and seemingly in order to get more funding from his foundation, CGIAR began merging all 15 of its centers into one legal entity in 2019. This move, overseen by a representative from the Gates Foundation and someone formerly of Syngenta, proceeded despite protests from the countries supposedly benefiting the most from CGIAR’s mission.

Gates also funds and controls DivSeek, which takes out patents on seeds after “mapping” their genomes and genome sequences. The practice of patenting seeds, which denies farmers the right to save seeds and researchers the right to conduct studies, robs farmers of their heritage and has been called “biopiracy.” It also appears to further a corporate takeover: DivSeek has sold its research and gene sequences to agribusiness giants Syngenta and DuPont.

Gates is also heavily invested in collecting seeds from around the world and storing them in the Svalbard Global Seed Vault — aka the Doomsday Vault, created to collect and hold a global collection of the worlds’ seeds. Based in Germany, the Crop Trust funds and coordinates the Svalbard Seed Vault, and is in turn funded by CGIAR, the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, and the three largest seed conglomerates.

In 2006, Bill Gates launched the Alliance for a Green Revolution (AGRA) to help small farms increase their yields — a common myth being that small farms have lower yields — and reduce hunger in target countries. An international study revealed that AGRA failed miserably at its stated goals: There is no evidence of any increase to small-scale producers’ yields or income, and in fact, undernourishment increased by 31 percent, negative environmental impacts are on the rise, and crop diversity has declined.

Though based at an ivy league school, this Gates-funded nonprofit’s alignment with agrichemical corporations has lost it a great deal of credibility. Graduates of its Global Leadership Fellows Program have gone on to positions in government and media in African countries, where, working in step with AGRA, they are known for pushing for investment-friendly policies while discrediting sustainable and regenerative practices in favor of biotechnology.

A new strand to Bill’s interconnected web of influence is Ag One, which aims to “provide smallholder farmers in developing countries, many of whom are women, with access to the affordable tools and innovations they need to sustainably improve crop productivity and adapt to the effects of climate change.” A seemingly admirable mission, but Gates has hired Joe Cornelius, a former executive at both Bayer and Monsanto, to lead it. The organization has drawn criticism from research groups in the seed and food sovereignty movement.

Taken together, these closely-linked endeavors are all driven by a transactional, tech-first, industrialized approach to agriculture, one that slowly but surely transfers knowledge, agency, and ownership over food production away from farmers and into corporate control. By spending billions on agriculture projects in African countries, Gates is attempting to launch another Green Revolution — one that prioritizes industrial methods like chemical inputs and genetically modified seeds.

Rather than feeding more people or helping small-scale farmers, where this revolution has had most success is in robbing African farmers of their independence. In an open letter, the International Panel of Experts on Sustainable Food Systems (IPES) pointed out the “loss of control over production choices” in countries where Gates-funded AGRA has focused its efforts.

This is chilling to anyone who watched the corporate takeover of the American farm system, where so many farmers are now at the mercy of powerfully consolidated corporations for what they can grow or raise, how they may operate, what inputs to use, where they may sell, and how much money they can make. AGRA is well-positioned to maneuver millions of independent producers into a state of dependence, and is brazenly helping its corporate partners tap into a huge market.

Gates has demonstrated that he does not care to listen or to collaborate. For example, under his direction, the newly-merged CGIAR continues to ignore evidence that agroecology is better at building resilience and is more economical for small-scale farmers. Development money from his foundation, supposedly for the improvement of African agriculture, consistently underwrites tech companies in the global north and dismisses the innovations and knowledge of African people.

This “Billionaire Knows Best” attitude has roots in colonialism, and Gates himself has been accused of conducting “philanthrocapitalism, which is boosting the corporate takeover of our seed, agriculture, food, knowledge and global health systems, manipulating information and eroding our democracies.” CGIAR and AGRA have scraped together further credibility by their involvement with the UN Food Systems Summit, which gives powerful transnational corporations an avenue to influence international food policies while promoting “solutions” that only serve their shareholders.

Despite all this corporate infiltration, resistance to Gates’s unwelcome meddling is gaining traction. The Seed Freedom movement has been calling for the CGIAR gene banks to return seed varieties back to the farmers. The largest farmer-led grassroots organization, the Alliance for Food Sovereignty in Africa (AFSA), resists AGRA’s influence and holds that agroecology is best for African countries; this has been supported by a major global study that revealed AGRA’s failures to deliver on its promises.

African producers can still evade the corporate grasp: According to researcher Tim Wise of Tufts University, “the vast majority of African food is still produced by Africans using seeds they’ve saved.” It’s not too late for African farmers and communities — not Bill Gates — to determine what’s best for African agriculture.

Meanwhile, Back in the U.S.: What About All That Farmland?

Even if Gates is buying vast swaths of farmland “just as an investment,” he is definitely contributing to a growing problem. There are concrete and verifiable consequences to absentee farmland ownership, whether it’s owned by an American corporation, a foreign corporation, or one solo billionaire:

- It increases land prices, creating a barrier for new or expanding farmers.

- It also empties and impoverishes rural communities, since distant owners do not reinvest their earnings from the land back into the community by shopping at local retailers, hiring community members, or relying on local services.

- A system that relies on leased farmland also robs wealth from the farmers themselves, no matter how good the lease terms may be. Farming does not provide farmers with an easy path to retirement; a farmer could lease land for a lifetime and end up with nothing, but land gives them equity in a stable and valuable resource.

- It is proven to discourage organic and regenerative farming practices: A farmer on a short-term lease isn’t going to invest in a long-term conservation measure, and land owners with no farming knowledge or experience don’t understand how important land conservation is for the viability of their asset.

- More abstractly but just as importantly, absentee farmland ownership is slowly but surely degrading our wealth of inherited agricultural knowledge. Historically, farmland has been passed down to the next generation, giving farmers an opportunity to transfer not only land but their own earned knowledge to the next generation. But corporations and absentee owners break that cycle — to our greater food system’s detriment.

Gates is also contributing to the concentration of power over a key component of the U.S. food system: the land itself. Though this country feels so big and our farmland seems limitless, we are actually losing about 2,000 acres of farmland a day. What’s more, half of it will change ownership in the next 25 years as farmers retire — giving corporations and billionaires like Bill Gates an opportunity to consolidate even more power over our food production.

Which leads to the real root of the problem: our food system is vulnerable to monopolistic control. Corporations and billionaires have been able to buy their way in and then influence how it works, affecting millions of people. In a more diversified and democratic system, no one entity could leverage this level of control and subject everyone else to the food security and national security risks associated with concentration.

How Do You Solve a Problem Like Bill Gates?

Will Harris, a fourth-generation farmer in Georgia, has publicly stated his concern over the dominance that Bill Gates — alongside a handful of corporations — has over the U.S. food and farm system. He thinks that Gates fundamentally misunderstands agriculture: Gates is accustomed to complicated linear systems (such as computers), not complex cyclable systems (such as farms, eco-systems, and bodies). In applying solutions to agriculture that would work excellently for a complicated linear system, Gates is bulldozing the food system’s resiliency and creating unintended consequences.

Ultimately, of course, we can’t know Bill Gates’s true intentions with the American food system. But based on the evidence here, we can draw some conclusions about his attitude towards regenerative farming — not to mention towards other people. At best, he is dangerously selfish and naive, not caring how his large-scale, high-tech experiments impact millions of less-powerful people, who never wanted these “solutions” in the first place. At worst, this power-hungry megalomaniac is seeking complete control over the world’s food supply — and is in a position to get it.

By implementing reforms that provide protections to farmers and ranchers and nurture our local and regional food systems, we can create a healthier, more democratic food system that works for us all.

Written and designed by Dee Laninga; edited by Angela Huffman, Joe Maxwell, and Sarah Carden; research by Sarah Carden and Dee Laninga; concept by Angela Huffman.