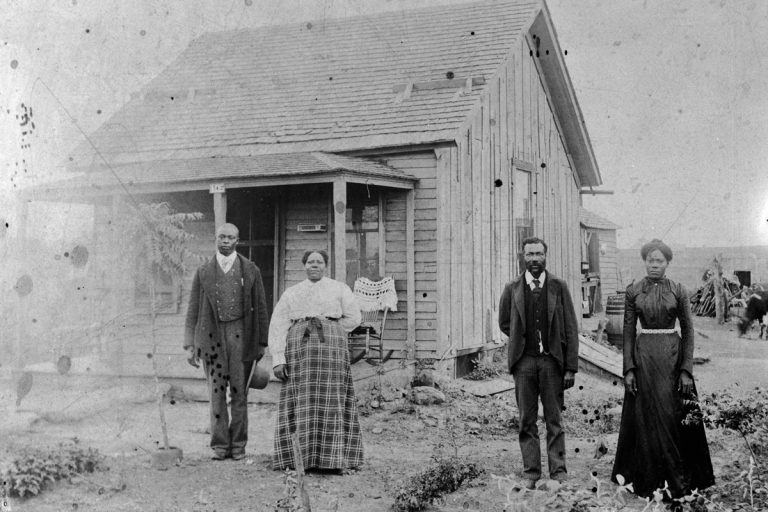

Nicodemus, Kansas is the oldest remaining African-American farming settlement west of the Mississippi. Alongside a winding two-lane country highway, the town hall, now a national parks site and museum, is a testament to the hopes and prosperity of the formerly enslaved people who walked more than a thousand miles almost 150 years ago to settle the ground that Nicodemus still sits on today.

The history of Black farmers in Kansas is complicated. On one hand, the story of Nicodemus is the unsung tale of Black prosperity in the early-20th century Midwest. Dr. JohnElla Holmes, president of the Nicodemus-based Kansas Black Farmers Association, acknowledges that many people outside of Kansas don’t know about the great migration of African Americans to the Midwest as early as the 1790s, followed by another mass migration about a century later. These settlers established over a dozen Black-led colonies in the free state of Kansas, owned land, and accumulated millions of dollars in wealth. By the late 19th century, there were more than 3,700 Black-owned farms in Kansas, and newspapers were widely promoting farming as a morally and economically sound way for Black families to establish generational wealth.

Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, HABS KANS, 33-NICO, 1-

On the other hand, Dr. Holmes expressed frustration with claims of ignorance over Kansas’s history of Black farmers. “People say, ‘Oh, what a beautiful hidden history.’ Well it’s not hidden history,” she said. “You know we’re out here beating the drums. We’re trying to get it out as much as possible.”

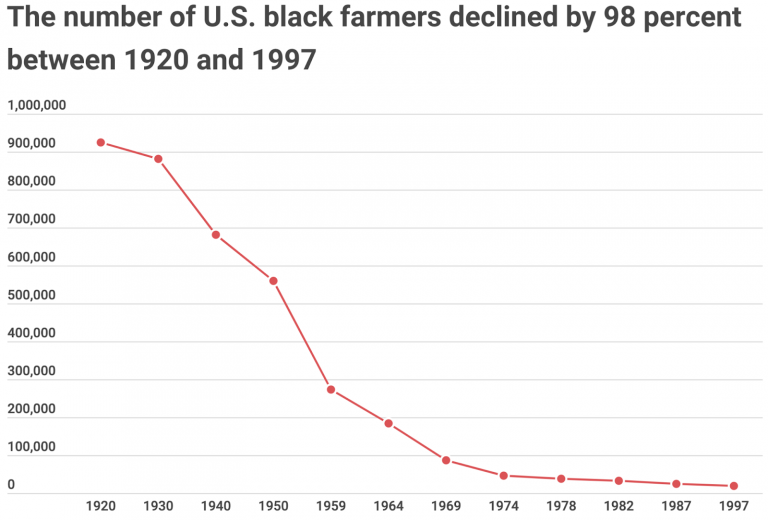

This lack of national awareness has had consequences. Since Dr. Holmes’ grandparents helped found Nicodemus in 1877, a lot has changed. After steady growth for about 40 years, the number of Black, land-owning farmers in Nicodemus and in Kansas at large has steadily declined. The reasons are plentiful: decades of federal policy and USDA discrimination, industrialization, the Great Depression, and the Dust Bowl all dealt blows to Black farmers who historically have a harder time accessing credit and loans. Market consolidation and anti-competitive policies have made matters worse in more recent years.

“Since 2000, we’ve lost over 18 Black farmers that owned land here. That’s close to 10,000 acres. [The] land loss has been devastating,” said Dr. Holmes. She pointed out that many of these lost Nicodemus farmers could not get farm numbers — identification numbers for farmland — from the USDA. “And without that farm number, you just can’t get in on any of the programs, you can’t get the assistance, you can’t get the technical help, you can’t get anything.”

Source: https://thecounter.org/usda-black-farmers-discrimination-tom-vilsack-reparations-civil-rights/

The Problem With Heirs’ Property

Black-owned land loss has been exacerbated further by heirs’ property laws. Heirs’ property is the legal system that transfers land to the descendants of its owner in the absence of official legal documents like wills or deeds. This method of passing down land was common in the semi-sovereign Black farming settlements of Kansas; however, issues can arise after successive generations when multiple children each own a fraction of the original piece of land. If one descendant decides to sell their piece, the law’s current mechanisms put all heirs at risk. The Black land loss resulting from these laws was recently documented by VICE.

In an effort to preserve the legacy of Kansan Black farmers, Dr. Holmes has been fighting for the passage of SB205, a state policy that would provide protections for any Kansan who has inherited heirs’ property. “Land ownership. That’s one of the most important things,” said Dr. Holmes, “and that seems to be the one thing that’s just slowly slipping through our fingers. You know, it’s ridiculous to think that in 1877, our ancestors owned more land than we do here in 2021. With all of our education, with all of our resources, we weren’t able to hold onto what [our ancestors] walked out here to get.”

Dr. Holmes hasn’t faced her fight alone. Kenya Cox, the recently-retired Executive Director of the Kansas African American Affairs Commission, successfully worked alongside Dr. Holmes and State Senator David Haley to introduce SB205 in the Kansas Senate. Dedicated to advancing any policy that will benefit African-Americans in Kansas, Ms. Cox and her seven non-partisan fellow commissioners have connected with advocates across the state to uplift their respective issues. When it came to the issues facing Kansas’ Black farmers, Ms. Cox collaborated closely with Dr. Holmes.

“Dr. Holmes and many of the Kansas Black Farmers [Association] members have really done a yeoman’s job in educating us about the barriers, the triumphs, and the great things that Black farmers are involved in,” said Ms. Cox. “This heirs’ property bill isn’t just something that will specifically help Black farmers. It will help all small Kansas farmers, across the state and across the region, because property ownership is a way to build that generational wealth. [This bill] gives us enormous potential and opportunity to eradicate poverty. When you have a property and you can pass that onto the next generation and the next generation, you can build that wealth.”

The Big Picture:

Federal Government and Black Farmers

Building generational wealth is something that has been historically difficult for Black families in the United States. Heirship issues aside, even families with clear-cut deeds and paid-off assets can lose their farms as they navigate complex USDA programs. Corellia Bradshaw-Johnson, a third generation Black farmer in Kansas, spoke about the challenges her family continues to face despite their relative success and unique access to financial resources through a white family friend and banker.

“When [my father] died we inherited our land from him,” she said. “The land was all paid for, the equipment was all paid for, but it was up to us to continue to be in the USDA program. I have a few sisters who did not know that, and they got kicked out of the program because they did not know what they needed to do every year. To this day, I have problems with USDA. There is a lot of red tape to go through. And if you don’t have someone, a mentor, then you’ll be frustrated. You’ll throw up your hands.”

Ms. Bradshaw-Johnson described being sent back and forth between different USDA county offices in Kansas to apply for the PPI program. Eventually, she had to travel to Washington D.C. to receive the help from the USDA she needed.

Corellia Bradshaw-Johnson and her late father, Paul Bradshaw

Recognizing the role that federal government agencies have played in the decline of Black farmers, federal policy makers like Senators Cory Booker and Raphael Warnock have introduced policies like the Justice for Black Farmers Act and the Emergency Relief for Farmers of Color Act, respectively. These bills represent a nationwide movement, an effort to raise up even ground for Black farmers to stand on. Both bills are currently introduced in the U.S. Senate, and some of their debt relief provisions were included in the American Rescue Plan Act. The effects of federal policies like this might seem nebulous, but it was the Pigford II settlement — a lawsuit that Black farmers won against the USDA due to decades of discrimination — that provided the grant funding necessary to launch the Kansas Black Farmers Association’s education and mentorship programs.

The Next Generation of Kansas’ Black Farmers

21 years later, the Kansas Black Farmers Association’s on-the-ground support continues to help Black farmers disrupt a century-long trend of land loss. But Dr. Holmes wants to go further than preserving existing Black-owned farms. She wants to call young Black people back to the tradition of farming and show them that there’s pride in the profession. “We want them to know that there’s no shame in farming anymore,” she said. “Don’t think slavery when you think farming. Think home ownership, land ownership. You’re your own boss. You’re the one that drives your own income. You are the one that can prosper. And there’s pride in that, you know? So we try to show them that.”

Under Dr. Holmes’ leadership, the Kansas Black Farmers Association has entered into their 13th year of an educational agriculture camp. The camp brings young inner city students to Kansas State University for two days, during which they meet professors and study agronomy at the college of agriculture; eventually, said Dr. Holmes, they learn that agriculture touches on every aspect of their lives.

The Kansas Black Farmers Association also runs a mentorship program where beginning Black farmers are connected with seasoned farmers who know how to plant and harvest crops — and just as importantly, how to navigate the business side of things, like applying for USDA programs. For women farmers, Dr. Holmes started up the Soul Soil Sisters, a program for women and advocates to share wisdom and support one another.

Dr. Holmes maintains that the greatest strength of Black farmers is in their unity. “Where we can work together. Where we can secure land again. Where we can be players in the game. And we can only get there with good education, with good solid laws that support us. Then I feel like the sky is just not going to be the limit.”

After attending a Soul Soil Sisters meeting, Kenya Cox praised the collaborative spirit that Dr. Holmes cultivates in the Black farming community, and the work she does to ensure that women especially can see themselves as farmers: “They stand with this determination, and with a commitment to ensuring that farming is something that is embraced and loved and passed on to future generations. It speaks to the foundation of who we are in Kansas. That perseverance and belief in the opportunity to do better and provide for your family.”

80 acres of wheat owned by Corellia Bradshaw-Johnson in Hodgeman County, KS

And while Kansans are unique in many ways, these leaders recognize that the struggles and strengths of Black farmers extend well beyond the state’s borders. From farming, to organizing and educating young farmers, to advancing policy that will keep farmers on their land, the positive changes manifested by Corellia Bradshaw-Johnson, Dr. JohnElla Holmes, and Kenya Cox benefit farming communities in Kansas and beyond. “[Dr. Holmes is] unapologetic in her advocacy…for Black farmers, but she realizes that many of the challenges and barriers, small farmers across Kansas are experiencing as well,” said Ms. Cox. “So working to bridge that divide and come together will strengthen us all. Rising tides lift all boats. We are the game changers, we are the trailblazers, we have set the standards that so many people across the nation have followed from the beginning.”

Support the Work

The work of Dr. JohnElla Holmes, Kenya Cox, and Corellia Bradshaw-Johnson is far from complete. Here is how readers can support their continued efforts:

Dr. Holmes encourages anyone who supports the Kansas Black Farmers Association’s mission to become a member. Readers can also buy from the Association’s shop. (Dr. Holmes highly recommends the Famous Nicodemus Pancake Mix.)

Ms. Cox asks that, regardless of what state they live in, readers reach out to their representatives to voice support for SB205 and other heirs’ property legislation. She stressed the importance of legislators hearing from their constituents, not just policy advocates like her. “Doing simple things like making phone calls, sending an email, or just sharing information about concerns around things that are happening in your community,” she said. “Agitate, speak out, and support, and remember to say thank you.”

Written by Anna Straus; designed by Dee Laninga; edited by Dee Laninga, Angela Huffman, and Joe Maxwell; concept developed by Joe Maxwell, Angela Huffman, and Anna Straus; outreach by Webster Davis.