On November 7, President Trump announced that he had directed the Department of Justice (DOJ) to investigate possible price manipulation and unfair practices in the beef industry. The announcement comes as the “Big Four” meatpackers—JBS, Tyson, Cargill, and National Beef—use their outsized power to squeeze ranchers and drive up beef prices for Americans.

This investigation is a welcome first step. But if policymakers are serious about standing up to abusive corporate power, they must go beyond an inquiry. Real reform will require strong enforcement to hold these companies accountable and break up the monopoly power controlling America’s cattle and beef markets.

What a DOJ Investigation Does

A DOJ investigation looks at whether companies have violated antitrust laws by fixing prices, limiting competition, or creating monopolies. Investigators can demand documents, question executives, and gather evidence of collusion or other unfair practices.

But too often, these probes end quietly. For this one to matter, it must end with enforcement.

Déjà Vu: Trump’s 2020 DOJ Investigation

This isn’t the first time President Trump has directed the DOJ to investigate meatpackers. In May 2020, during his first term, the DOJ’s Antitrust Division investigated the same four companies after cattle prices collapsed during the pandemic while beef prices soared.

But publicly, the investigation produced no major enforcement actions or reforms—underscoring how critical it is that this round does not end the same way. Five years later, the same corporations dominate the market. This time, the DOJ must dig deeper into the collusion and political influence that define this industry.

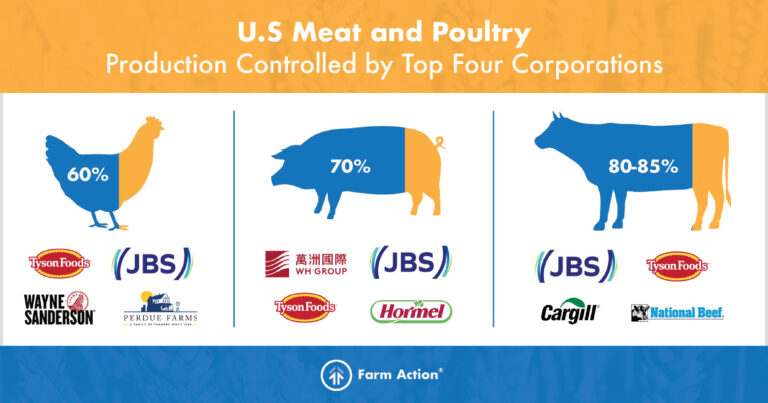

Just four corporations control the vast majority of U.S. beef, pork, and poultry processing.

The Meat Monopoly

Just four corporations—JBS, Tyson Foods, Cargill, and National Beef—control roughly 85% of the U.S. beef processing market. They also dominate the poultry and pork sectors, giving them enormous control over the American meat supply.

With that dominance, they dictate terms from ranch to grocery shelf, pushing ranchers to accept lower prices for cattle while charging consumers more for beef. Since 1970, ranchers have gone from earning about 70 cents of every beef dollar to just 37 cents, while corporate profits have soared.

Independent producers have been sounding the alarm for years. Bill Bullard, CEO of R-CALF USA, the nation’s largest producer-only cattle association, welcomed the new investigation, saying the gap between cattle and beef prices is “evidence of market failure.” His comments echo what ranchers across the country have long warned: consolidation has gutted competition, leaving producers with fewer options and less power in the marketplace.

Price Fixing and Market Manipulation

The Big Four have repeatedly been accused of conspiring to limit cattle supply and inflate beef prices. These allegations span years and lawsuits, showing an industry that treats collusion as a business strategy.

This year, JBS agreed to pay $83.5 million to settle a lawsuit filed by ranchers who said the company conspired to manipulate prices. Tyson has faced similar suits and settlements. For corporations this large, fines are just the cost of doing business.

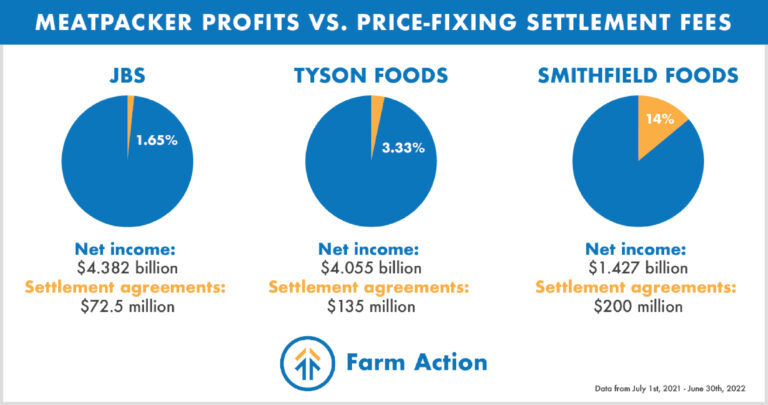

In 2022, JBS earned $4.4 billion in profit and paid only $72.5 million across two settlements—less than 2% of its gains. Tyson made $4 billion and paid roughly $135 million, about 3% of its profits.

True accountability means more than fines—it means breaking up monopolies and restoring fair competition. But the reason these companies continue to get away with it goes beyond the marketplace—it’s rooted in political power.

The Big Four’s price-fixing fines are tiny compared to their profits.

Political Influence: How Power Protects Power

JBS’s rise shows how monopoly and political power feed each other. In 2017, investigations revealed that JBS’s owners, the Batista brothers, bribed more than 1,800 Brazilian politicians to secure loans that fueled their global expansion, including into the U.S.

Once established here, JBS became a political powerhouse. Earlier this year, a JBS-owned firm made the single largest donation—$5 million—to President Trump’s inaugural committee and doubled its lobbying spending. Tyson and Cargill have followed similar paths, pouring millions into campaign contributions to protect their dominance. And in June, JBS was listed on the New York Stock Exchange, gaining even more capital to consolidate control.

This political capture explains why investigations so often fizzle and fines stay small. Breaking up the Big Four isn’t just an antitrust issue—it’s about reclaiming democracy from corporate control.

What the DOJ Could Be Looking For

If this investigation is going to matter, the DOJ must dig into how the Big Four manipulate cattle and beef markets through coordinated control and retaliation. Here is where to start:

Restricting Supply: Investigators should examine whether packers collectively slowed slaughter lines or reduced capacity to push cattle prices down and boost margins. Even small, simultaneous cutbacks can distort the market.

Parallel Pricing: DOJ should look for patterns where packers move prices together, stop bidding at the same time, or avoid bidding against one another—classic signs of collusion when tied to shared communications or data.

Cash Market Manipulation: Packers use the small cash market to set national prices while relying on captive supplies and secret contracts. DOJ must determine whether they deliberately thin this market to suppress prices paid to ranchers.

Contract Control: Alternative Marketing Agreements (AMAs) can function as exclusive deals that lock ranchers into one buyer and give packers advance knowledge of supply they can use to manipulate prices.

Information Sharing: Any exchange of future plans—such as slaughter schedules, procurement volumes, or pricing intentions—should raise alarms. In such a concentrated industry, even “informal” coordination can act like a cartel.

Abuse and Exclusion: Producers who resist packer demands often face retaliation through delayed pickups or refusals to buy. DOJ should also investigate whether packers use contracts and logistics control to block smaller processors.

Hidden Ties and Repeat Offenses: The industry’s long history of collusion warrants a close look at shared ownership, joint ventures, and repeated anticompetitive behavior across beef, pork, and poultry.

What the DOJ Can Do

If investigators uncover anticompetitive behavior, the DOJ has powerful tools to act. Under the Sherman Antitrust Act, it can take the packers to court, break them up, prosecute executives, force changes that protect farmers, and prevent further consolidation.

The DOJ should also coordinate with the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) to enforce the Packers and Stockyards Act, which bans unfair and retaliatory practices that harm farmers and ranchers. Strong enforcement would prevent packers from punishing independent producers and restore transparency to cattle markets.

The law is clear; what’s been missing is the political will to use it.

The Big Four own most of the meat brands on U.S. shelves, from beef to pork to poultry.

Zooming Out: What Else Needs to Be Done

Even the strongest DOJ action won’t fix this system alone. Congress and the administration must rebuild the conditions for fair markets—transparency, regional processing, and public investment in independent producers.

Restore Mandatory Country of Origin Labeling (MCOOL): Millions of pounds of imported beef enter the U.S. each year without labels, undercutting American ranchers. Congress should reinstate mandatory labeling through the the American Beef Labeling Act (S. 421) or the Country of Origin Labeling Enforcement Act (H.R. 5818), and the administration should use the 2026 U.S.–Mexico–Canada Agreement review to restore MCOOL protections for meat traded across North America.

Reform Alternative Marketing Agreements (AMAs): Packers use secretive contracts known as AMAs to control cattle supplies and weaken the open cash market, leaving ranchers with little power to negotiate fair prices. USDA can restore transparency and competition by making the Cattle Contracts Library permanent, limiting exclusive deals, stopping contracts tied to future cash prices, and ensuring more cattle are sold on the open market.

Support Small Processors: Pass the PRIME Act (S. 2409) to give farmers more market options by allowing them to sell meat processed in their state custom facilities directly to consumers without federal inspection. Expanding this flexibility—and investing in small and mid-size plants—would rebuild regional processing capacity and keep more of the food dollar in rural communities.

Reform Government Food Procurement: Each year, the U.S. government spends billions on food—but most contracts go to the same corporate giants, including Cargill, Tyson, and JBS. This practice uses public money to entrench monopoly power. By prioritizing independent farmers and ranchers in its food purchases, the government could use those dollars to support fair markets and resilient regional food systems instead of enriching global conglomerates.

A Moment for Real Reform

The new DOJ investigation shines a light on a long-broken industry. But we’ve been here before. If this effort ends like the 2020 probe—with no accountability and no structural change—ranchers and consumers will keep paying the price.

The DOJ must use its full authority to break up the Big Four meatpackers and restore real competition. Nothing less will stop these corporations from squeezing ranchers, driving up prices, and corrupting our food system.

This is the moment for bold reform to rebuild fair markets and return power to the farmers and ranchers who feed this nation.