America’s food system didn’t become dominated by a handful of powerful corporations by chance. Today’s extreme consolidation, exposed throughout our Food Monopoly Files series, was built through a deliberate, decades-long expansion of corporate power.

That expansion was made possible because, beginning in the 1980s, the federal government weakened the antitrust rules that once kept markets competitive. With regulators adopting a corporate-friendly mandate, wave after wave of mergers swept across the economy. Agriculture was no exception.

Freed from meaningful oversight, corporations at every level of the food chain deployed the same strategic blueprint to take control of markets, influence public policy, and reshape the rules in their favor. This “corporate playbook” isn’t a metaphor—it’s a consistent pattern that engineered and entrenched monopoly power. The consequences for farmers, rural communities, and consumers have been profound.

Step One: Consolidate the Market Until Competition Becomes Impossible

The first and most foundational move is to eliminate competitors—not through innovation, but through scale. Once antitrust enforcement weakened in the 1980s, agribusiness corporations were effectively given a green light to merge, acquire rivals, and vertically integrate across entire supply chains. Deals that would once have been blocked for concentrating market power were waved through, allowing dominant firms to grow larger while independent competitors disappeared.

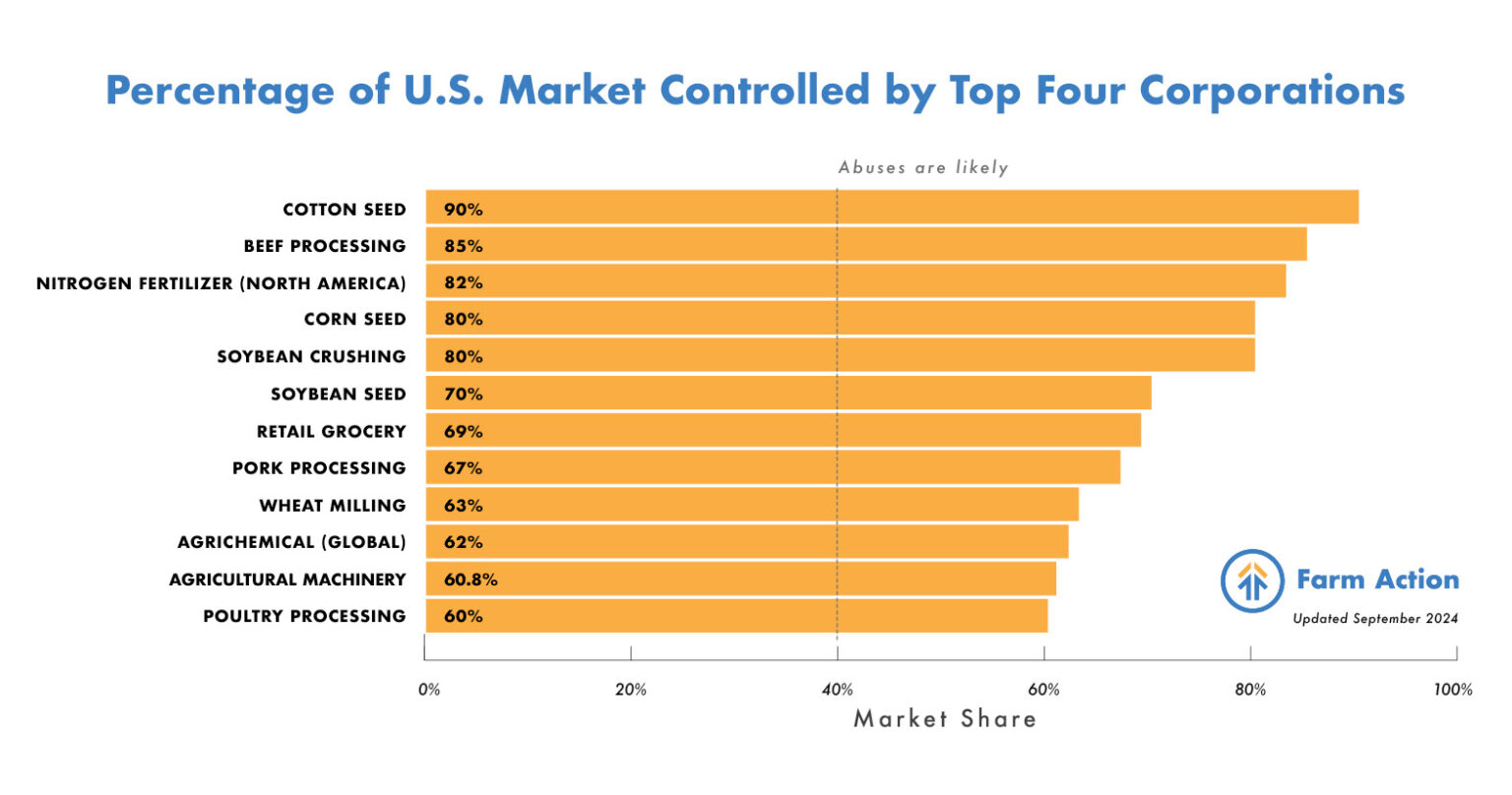

The results today are staggering:

- Four companies control 85% of beef packing and 70% of pork processing.

- Just two manufacturers control nearly 90% of the tractor and combine market.

- Four corporations dominate the U.S. seed and global agrichemical sectors.

This widespread consolidation didn’t just reduce the number of companies in the market—it fundamentally shifted who held power. With fewer companies to sell to and fewer suppliers to buy from, corporations gained the ability to dictate prices, contract terms, and access to markets, leaving farmers and producers with little leverage and few alternatives.

Step Two: Create Farmer Dependency Through Contracts, Patents, and Technology Locks

After reducing competition, corporations deploy tools that lock farmers into dependent systems.

In the poultry sector, contract growing has stripped many farmers of autonomy. Integrators—major poultry processors—control the entire production process, from hatcheries and feed to processing and retail, while farmers shoulder the debt and risk. Consolidation allows a few dominant corporations to impose contract terms that give them outsized, often abusive power, leaving farmers with little choice but to accept them.

Seed and chemical companies such as Bayer-Monsanto perfected a different kind of lock-in by patenting genetically engineered seed traits and bundling them with proprietary chemicals like Roundup. Farmers who once saved and replanted seed found themselves legally barred from doing so, forced to repurchase seed each year under strict licensing terms that stripped them of autonomy and drove up costs.

At the same time, equipment manufacturers like John Deere followed suit, embedding software locks that block independent repair and force farmers back to the dealer for even basic fixes.

These systems drain wealth from rural communities, concentrating control while stripping farmers of independence.

Step Three: Capture or Influence the Institutions Intended to Represent Farmers

As consolidation deepened, corporations learned to manipulate the very organizations meant to give farmers a collective voice.

Mandatory commodity checkoff programs provide a clear example. Originally created to fund research and promotion for commodities like beef, pork, dairy, soybeans, and eggs, checkoffs now extract nearly $1 billion in mandatory fees each year from producers. But investigations—including those conducted by Farm Action—have revealed that these funds often benefit the largest corporate players at the expense of independent farmers.

The result: Organizations positioned as the “voice of farmers” routinely support policies that entrench corporate consolidation, reduce competition, and suppress farmer livelihoods.

Step Four: Shape the Public Narrative to Mask Harm and Legitimize Power

After consolidating markets and capturing institutions, corporations must prevent public backlash. They do this by shaping how consolidation itself is understood by farmers, consumers, policymakers, and the press.

Agribusiness giants consistently reframe market concentration as a public good. Consolidation is sold as “efficiency,” and corporate scale is justified as necessary to “feed the world”—even though the U.S. is reliant on importing nutritious fruits and vegetables from other countries. These narratives present monopoly power as not only inevitable but also benevolent, deflecting attention from how consolidation suppresses farmer pay, strips producers of choice, and shifts risk onto rural communities.

Advertising campaigns reinforce this framing by promoting increased consumption while avoiding any discussion of who controls agricultural markets, how prices are set, or who benefits from consolidation. At the same time, industry-backed trade associations position themselves as neutral, science-based authorities, dismissing farmer concerns as anecdotal and portraying corporate dominance as the natural outcome of modern agriculture.

With far fewer resources, independent farmers and watchdogs struggle to challenge these narratives, narrowing what solutions the public and policymakers see as possible and clearing the way for policies that entrench corporate power.

Step Five: Influence Policymaking to Reinforce Corporate Dominance

Finally, corporations ensure their dominance becomes self-perpetuating by embedding themselves directly within the policymaking process. Revolving doors between industry and government place corporate-aligned officials in regulatory roles, while lobbying shapes farm bills, trade agreements, labeling rules, and antitrust enforcement.

But this is not a modern phenomenon. A century ago, members of Congress warned that the USDA itself had become so entangled with the meatpacking giants that it could no longer conduct a “genuine investigation” into the industry it regulated. Decades of personnel swaps between agribusiness, corporate law firms, and regulatory agencies entrenched a culture that treated monopoly as efficiency and consolidation as inevitable—leaving farmer harm dismissed as collateral damage.

Across decades, these efforts have eroded the tools that once protected farmers and consumers from monopoly abuses. Antitrust enforcement weakened. Merger review became permissive. And corporate-written policies enabled the concentration we see today.

Today’s food monopolies were not accidental. They were built. And they were built by following the same strategic blueprint again and again—one that consolidates control, extracts wealth, silences independent voices, and reshapes public institutions to serve private interests.

Understanding this playbook is essential to dismantling it.

This post, like the rest of our Food Monopoly Files series, draws from Kings Over the Necessaries of Life, our landmark investigation into how monopoly power reshaped U.S. agriculture. Next up, we’ll turn to the human cost of consolidation—how farmers, workers, and rural communities are paying the price.