In the first two posts of our Food Monopoly Files series, we looked at how monopoly agriculture took root in the U.S. and how just four meatpackers came to control the beef industry. But monopoly power extends far beyond meat processing—it begins in the ground, with the seeds farmers are allowed to plant.

When Corporations Own the Inputs

For thousands of years, humans have saved and shared seeds from their harvest to plant for the next season. This cycle gave farmers and agricultural communities independence, resilience, and the ability to adapt crops to their local soil and climate. But in just a few decades, that age-old practice has been upended.

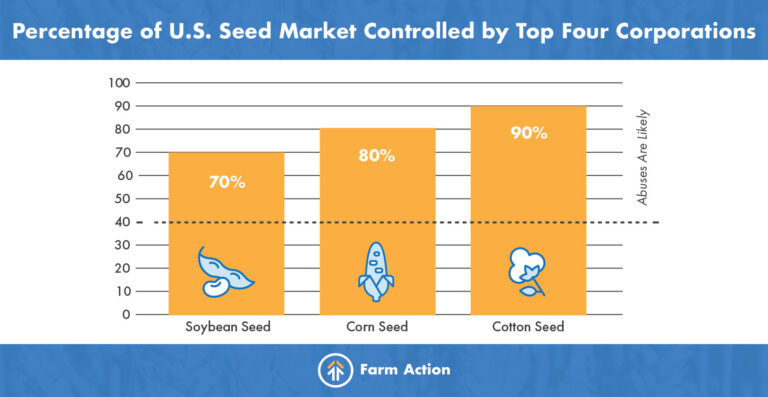

Today, just four corporations—Bayer, Corteva, ChemChina, and BASF—control more than 50% of the global seed market, consolidating power with their patented genetically engineered seeds. Bayer and Corteva control the U.S. soybean, corn, and cotton seed markets even more tightly. The same corporations that control seeds also control the pesticide market. By engineering seeds to work hand-in-hand with their own branded chemicals, they’ve created “technology packages” that ultimately lock farmers into buying both.

When corporations control the seeds, the chemicals, and the patents, farmers lose control over their most basic tools. Licensing agreements ban seed saving and tie seeds to chemical technology packages, leaving farmers locked into systems they may not have otherwise chosen. Even if they’d prefer other seeds or fewer chemical inputs, corporate patents and market control restrict access and force dependence on a narrow set of costly options.

Patents Over People

How did this shift happen? In the 1980s and 1990s, a series of court decisions and regulatory changes allowed corporations to patent not only genetically engineered seeds, but also to extend patents that cover plant varieties, breeding methods, genetically modified traits, and germplasm, which carries genetic material. These patents transformed seeds from a renewable resource into a product farmers had to buy every year.

Take Monsanto’s Roundup Ready soybeans, introduced in 1996. The seeds were genetically engineered to withstand glyphosate, Monsanto’s blockbuster herbicide. Farmers who planted Roundup Ready soybeans signed contracts barring them from saving or reusing the seeds. Instead, they had to buy new ones each season, along with the matching herbicide.

The model was so profitable that competitors followed suit. Mergers and acquisitions consolidated the seed industry into just four giants, each offering technology packages that bundle seeds with their corresponding pesticides. Today, this seed-chemical treadmill extracts billions from farmers while eroding their independence.

Farmers Trapped in the System

The impacts on farmers are stark. Seed and pesticide prices have skyrocketed as corporate giants tighten their grip, with genetically engineered seed prices rising far faster than non-genetically engineered alternatives. On top of that, farmers face significantly reduced options in the marketplace, often forced to buy seed traits they neither want nor need.

At the same time, resistance to weeds, diseases, and pests has emerged. Rather than developing new ways to combat resistance driven by a production model that relies on decades-old chemicals, seed corporations simply stack on additional traits to these seeds, knowing that new resistance will continue to emerge.

Even farmers who wouldn’t otherwise choose genetically engineered seeds are often forced to buy them because of herbicide drift, which occurs when the wind carries herbicides, sometimes miles from where they’re sprayed, ruining unprotected fields and killing crops. In cases like these, farmers often adopt the same practices as their neighbors in order to protect their harvests.

For many farmers, there’s simply no way out. The contracts are binding, the alternatives limited, and the risks of stepping outside the system too high. Those who try to save seeds or reuse them risk lawsuits from billion-dollar corporations.

Consumers Feel It Too

Seed and pesticide consolidation isn’t just a farmer problem—it affects consumers, too. Higher input costs ripple through the supply chain, raising the price of food at the grocery store. And when farmers can’t keep up with skyrocketing input costs and low commodity prices, taxpayers are often left footing the bill through massive farm bailouts. Billions of dollars are spent propping up a system designed to enrich a few corporations—costs that ultimately land on the public, while families still face higher food prices.

Meanwhile, corporate control reduces crop diversity, leaving shoppers with fewer choices and a food system more vulnerable to shocks like pests, disease, or extreme weather.

Similarly to the meatpacking industry, the illusion of choice is everywhere. Multiple seed brands available to farmers may look like competition, but they often trace back to the same corporate parent. Whether it’s soybeans, corn, or cotton, a handful of companies are setting the terms for what gets planted on millions of acres.

Beyond higher prices and fewer options, corporate control over seeds and pesticides also carries public health risks—from increased chemical use to reduced access to nutritious, diverse foods.

A Broken Market by Design

This system isn’t the natural result of innovation—it’s the product of deliberate policy choices. Weak antitrust enforcement allowed mega-mergers like Bayer’s takeover of Monsanto to proceed, even though regulators knew the risks to competition. Intellectual property laws have been misinterpreted to favor corporate ownership of seeds, sidelining farmers’ traditional rights.

And as always, corporate lobbying power ensured that policymakers looked the other way. The result is a food system where the most basic input—the seed—is controlled not by the farmers who plant it, but by corporations that profit from keeping them dependent.

Time to Plant Something New

The story of seeds and pesticides is another chapter in how monopoly agriculture extracts wealth from farmers and consumers while consolidating power at the top. But it doesn’t have to be this way. Just as Americans called on Congress to fight meatpacking monopolies a century ago, we can reclaim control of our seed supply and restore fairness to the system.

Farm Action is working to expose the abusive levels of power just a handful of corporations have over seed and pesticide markets—and to push for policies that restore farmer independence and consumer choice. From enforcing antitrust laws to reforming intellectual property rules, we have the tools to rebuild a system that works for people, not just corporations.

This post, like the rest of our Food Monopoly Files series, draws on Kings Over the Necessaries of Life, our landmark investigation into how monopoly power reshaped U.S. agriculture. We’re breaking that research down sector by sector to show how corporate control works—and how we can build something fairer in its place.

Next up: fertilizer. We’ll examine how three corporations gained a chokehold on one of the most relied-upon farm inputs, and how that power drives up costs for everyone.