On Feb. 6, 2026, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) reapproved dicamba for use on soybeans and cotton for the 2026–2027 seasons. EPA says this label has its “strongest protections” yet. But dicamba’s track record is drift damage and community conflict, because farmers have been boxed into a system where one neighbor’s weed control can become another neighbor’s loss.

The following excerpt on dicamba impacts is adapted from our 2020 report, The Food System: Concentration and Its Impacts, and has been condensed for clarity and brevity.

Dicamba Debacle: “The herbicide for which Mike Wallace literally gave his life”

Dicamba, registered as an herbicide in 1967 and available in 1,000 products in the U.S., has recently pitted farmer against farmer and farmer against community, as well as given “all of agriculture a black eye” in the words of one weed scientist.

In the five years since Monsanto’s (now Bayer’s) Xtend dicamba resistant soybeans was approved, all of the large agrochemical-seed firms introduced dicamba-tolerant seeds, including ChemChina, Corteva, BASF and Bayer. In the same time period, the Heartland has witnessed one related murder, thousands of dollars of uncompensated off-target injuries, and failure of institutions to combat the power of agriculture firms.

Power Play

In 2015, Monsanto rolled out dicamba-tolerant soybeans before a less-volatile dicamba formulation was approved. That created a predictable problem: older dicamba products were prone to drift, and in practice some farmers used them anyway, leading to widespread off-target damage. Even though those formulations weren’t approved for use on growing soybeans, the company continued selling the seeds and seemed to blame farmers when widespread crop damage followed.

Court documents in a farmer’s lawsuit against Bayer and BASF suggest that the companies “created circumstances that damaged millions of acres of crops by dicamba in order to increase profits.” Although newer dicamba formulations were approved by 2017, crop damage linked to the herbicide continued.

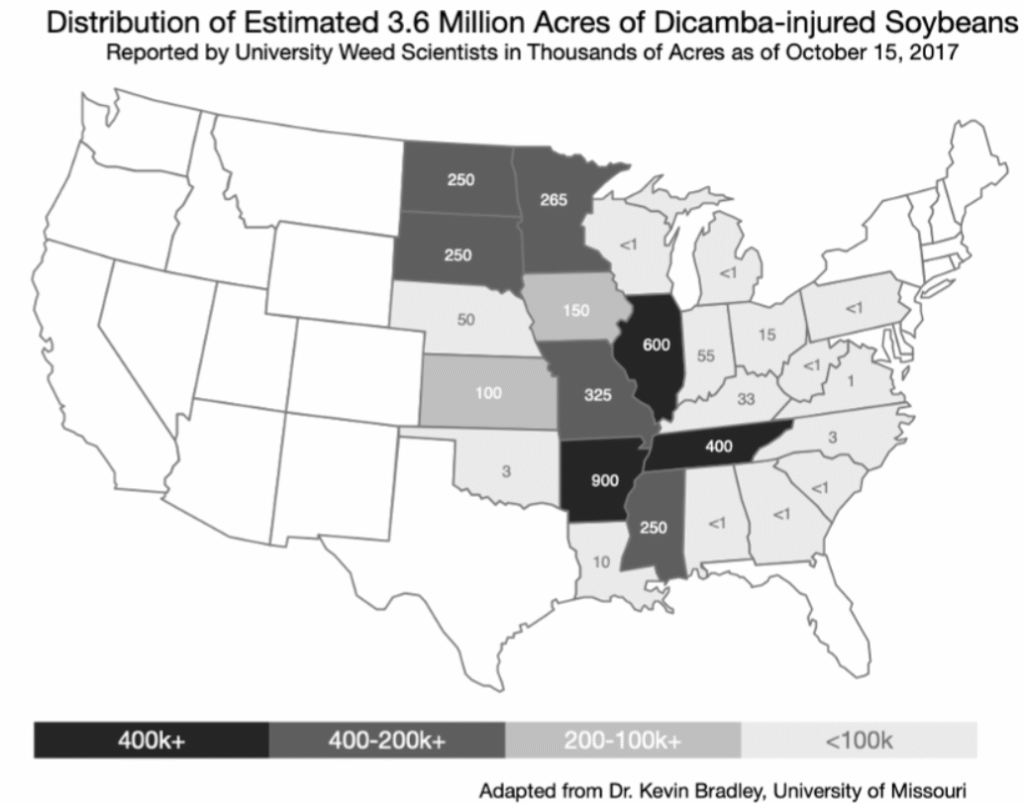

Distribution of dicamba-related soybean injuries known in 2017.

There were reports of so-called defensive planting, whereby farmers protected themselves from neighboring farmers’ use of dicamba by planting Xtend or other dicamba-tolerant soybeans – especially if the price was not substantially different than other traited seeds.

“‘I had to start growing dicamba beans because the losses were so much you can’t stand it,’ said Sam Branum, a recently retired farmer near Hornersville [MO]. ‘If you’re farming around it, you either get with it, or you get out.’”

Another Missouri farmer, Carlis McHugh, said “We switched over to it to protect ourselves…You didn’t have a hell of a lot of choice, if you know what I mean.”

While dicamba resistant soybeans were widely planted from 2017-2020, largely because of resistant weeds like waterhemp and Palmer amaranth, problems with dicamba use remained. Weed scientists at the University of Missouri detailed potential problems with volatility even with new formulations.

In February, 2020 a jury awarded Bader Farms, a peach orchard, $15 million in compensation for damages from off-target dicamba drift, and awarded over $200 million more in punitive damages.

In June, the agriculture community was stunned when a federal court ruled that EPA’s approval of reformulated dicamba (XtendiMax, Engenia and FeXapan) in use on “an estimated 60 million acres of soybeans and cotton [was] vacated – or ended – effective immediately.” Farmers could apply any existing stocks of those herbicides through July 31, 2020.

Community Impact

The volatility of dicamba has pitted neighbor against neighbor in rural communities. The most poignant, of course, is the murder of Mike Wallace by his farming neighbor’s employee, Curtis Jones, over dicamba drift damage to an estimated 40% of Wallace’s crops. In the months after this murder, Wallace’s family worked to get a permanent ban on dicamba, “a quest that has put Wallace’s family at odds with many of their neighbors.”

Others acknowledge the potential community problems, as this Arkansas farmer said in 2017:

“We’re trespassing on our neighbors, and we’re trespassing on our neighbors in town. It’s not just our neighbor farmers. There’s a lot of damage in yards. You hate to say that and call attention to it, but it is a reality.”

In 2018, just two years after dicamba-tolerant beans were introduced, an investigation by the agricultural news service DTNPF on community impacts of dicamba drift exposed the destruction of a South Dakota CSA farm’s crops, a Tennessee rural resort struggling to save gardens and trees, and an Illinois homeowner who spent at least $10,000 investigating damage from dicamba on her “carefully landscaped yard.”

In all these cases, individuals – in the first two instances, consumers and farmers attempting to build agrifood alternatives – were blindsided by the constrained choices of conventional farmers.

In essence, the rights of rural community members to make choices about their livelihoods or even their enjoyment of rural properties is usurped by the right of dominant agrifood companies to profit or of conventional row-crop farmers to control weeds.

Perhaps the situation is best summed up by a Missouri farmer interviewed in 2019:

“With Dicamba, you can do everything right and it can still move around and damage the neighbor’s orchard or the garden of the lady down the road….morally, can you spray a product that you have no control over once it leaves the boom tip and you have to rely on Mother Nature to keep it where it's at and you damage someone else's crop?”

Failure of Institutions

The power of these dominant firms is also demonstrated by the failure of the EPA and state agencies to regulate dicamba, and the struggle by universities to provide accurate information about its use.

University weed scientists were caught off-guard as dicamba related injuries accumulated in 2016 and 2017. Some state agencies have been in the crosshairs between corporate power, desperate farmers, and community concerns.

For instance, after the Arkansas Plant Board restricted use of dicamba-based herbicides in 2016 and 2017, Monsanto sued the board “arguing that the 2016 rule had effectively prohibited in-crop use of XtendiMax in 2017, and that the 2017 rule would effectively prohibit in-crop use of XtendiMax in 2018.” At the same time, farmers also sued the board after it set an early April, 2018 cut-off date for spraying dicamba instead of the May 25 date.

Other state agencies responsible for regulating herbicides issued and rescinded bans limiting use at certain times, and pleaded with EPA to ban post-emergent use when reregistering the chemical. States were flooded with damage reports, even though some farmers felt state agencies were reluctant to investigate and even discouraged reports. The federal judiciary stepped in, vacating EPA’s approval of three specially formulated herbicides in the middle of the 2020 growing season.