Article originally published September 26, 2022. Updated in November 2025.

Whether you live in farm country or in the city, you’ve probably noticed the quality of produce at your local supermarket has deteriorated over the years. These days, our “fresh” produce isn’t actually fresh at all—much of it has been picked too early, shipped across land and sea, and delivered to your grocer with a “Product of Mexico” or “Product of China” sticker tacked onto it.

As Farm Action’s Angela Huffman explained on CNBC, the United States is growing less and less of its own food and is becoming increasingly dependent on foreign countries to feed itself as a result.

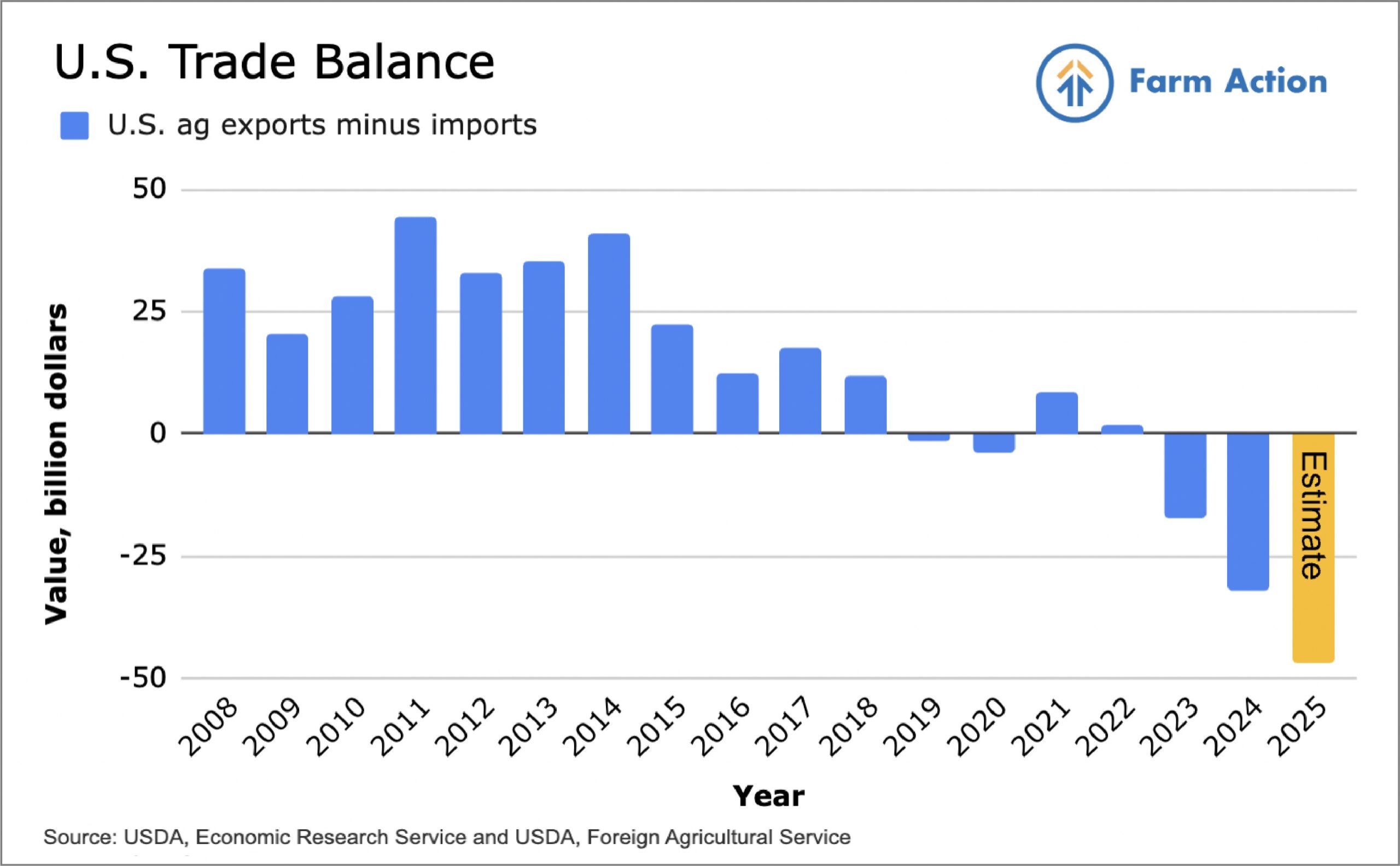

The U.S. used to be a proud agricultural powerhouse, consistently running an agricultural trade surplus. But in 2019, for the first time in more than 50 years, the mighty U.S. agriculture system ran an agricultural trade deficit, importing more than it exported: Though we racked up a $9.7 billion agricultural trade surplus with the rest of the world, our $11 billion agricultural trade deficit with Mexico resulted in a $1.3 billion deficit overall.

Years later, this imbalance has become a trend, with the U.S. running an agricultural trade deficit for five of the last seven years. The projection for 2025 was worse than ever, with a deficit of $47 billion.

This growing deficit is driven by our dependence on more fruit and vegetable imports from other countries. For example, in 2019, we imported $15.7 billion worth of fruits and vegetables from Mexico. In 2023, our fruit and vegetable bill from Mexico shot up to $34.3 billion. Big Ag corporations perpetuate the myth that industrialized agriculture is necessary so the U.S. can “feed the world.” How could we even begin to aspire to “feed the world” if we can’t feed our own country? We need to balance our own books first.

We Want Food, Not Feed!

The U.S. is focused on growing and exporting low-value corn and soybeans, and this comes at the cost of America’s economic security and the public’s health. Corn and soybeans are not the staples of healthy food for people—their primary uses are for livestock feed, ethanol, and to make cheap sugars, starches, and oils that end up in highly processed junk foods. Big corporations and the U.S. government have created a system where we need to buy our fresh produce from other countries instead of growing it in American soil, and we are giving away opportunities as a result.

Forgone Economic and Public Health Opportunities

As competition from imports has grown, it has negatively impacted food and farm industries, with producers increasingly going out of business or shifting operations outside of the U.S. Over the last two decades, the percentage of U.S. fruit and vegetable supply that is imported has surged: Between 2000 and 2023, tomatoes have gone from 30.02% to 68.87% imported, cucumbers from 42.56% to 89.14%, and bell peppers from 33.8% to 73.89%. It’s easy to look at the data and just see numbers, but those numbers represent farmers who are losing their livelihoods. What’s more, all the jobs and economic benefits supported by local supply chains are disappearing along with those farms.

Fruits and vegetables are higher-value products than the corn and soybeans the that U.S. food and farm system currently prioritizes. Even though the soybean industry receives substantially more government support, its industry value is estimated at 20% lower than that of fruits and vegetables.

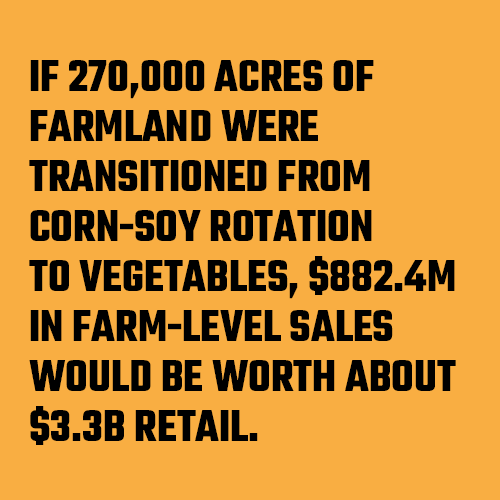

According to our research, fruits and vegetables also require less acreage to turn a profit: If 270,000 acres of Midwest farmland (about the size of a county) were transitioned from corn-soy rotations to vegetable production, $882.4 million in farm-level sales would be worth about $3.3 billion when sold at retail. This would create more opportunities for young and beginning farmers who struggle to gain access to land.

Today, the U.S. faces a nutrition crisis. Despite the fact that we currently import a third of our vegetable and two-thirds of our fruit supplies, 90% of the U.S. population still falls below the recommended dietary allowance (RDA) for vegetables, and 80% fall below the RDA for fruit. The U.S. government’s lagging support of fruit and vegetable production compared to commodity crops is reflected in Americans’ food access. In our current food system, fresh produce is more expensive and more difficult to access than unhealthy, processed foods.

When provided with better access to fruits and vegetables, studies have shown that consumers increase their intake. If we want to improve our citizens’ health, we need to expand access to fresh produce—but how will we supply that increased demand? In our current system, we’d need to increase produce imports even more. Let’s instead change our domestic food and farm system supports so that our farmers can grow healthy produce for their fellow citizens.

Why Would We Leave All These Opportunities on the Table?

We’re missing out on key opportunities to bring jobs back to rural communities, enable new generations of farmers to make a living with less land, and improve public health. Who wouldn’t want these changes? It’s the Big Ag corporations and trade associations that have seeded their money and influence throughout the food and farm system to prioritize the production of livestock feed over healthy food. As a result of their influence, our government provides the bulk of its farm supports to corn and soybeans: the low-value products that result in feed for livestock (which is funneled into meat exports and the pockets of giant corporations); unhealthy, hyper-processed food; or ethanol.

Meanwhile, the Mexican government supports fruit and vegetable production through government subsidies, and their produce exports are booming. This goes to show: If the government supports it, producers will grow it. U.S. farmers are on a treadmill in our current system, which is crafted to benefit Big Ag over everyone else. Farmers need support to transition out of this system so they can feed their neighbors and make a living for themselves, which can be accomplished by shifting our farm subsidies.

We Need to Stop Outsourcing What We Could Grow Ourselves

The current industrial monoculture system is forcing us to outsource what we could grow ourselves, denying opportunities for the next generation of farmers, impoverishing communities, and making Americans sick.

Many in Washington, D.C. continue to push for exporting our way out of this trade deficit, but that would only be doubling down on what we’re currently doing wrong. Rather than increasing our exports, we should reduce our imports by producing more of our food on U.S. soil.

Farm Action’s 2023 report discussed how we can balance our deficit by growing more of our own food crops. Shifting less than 0.5% of current farm acreage to fruits and vegetables would have balanced 2024’s $32 billion trade deficit because fruits and vegetables are much higher-value crops than corn and soybeans.

We need to start growing more of our own food on U.S. soil again. This starts with the government shifting its support towards the higher value, essential food crops we need to feed ourselves. Shifting farm subsidies towards diverse production models that include fruits and vegetables would support the development of a local- and regionally-based network of diversified farms feeding and enriching their communities, and putting more money in the pockets of farmers instead of multinational corporations.

Written by Jessica Cusworth, Dee Laninga, and Sarah Carden; concept developed by Joe Maxwell and Angela Huffman