Introduction

Most Americans have no idea what’s behind catchy slogans like “Beef. It’s What’s for Dinner” or “The Incredible, Edible Egg” or “Pork. The Other White Meat.” These famous promotional campaigns — that we’ve quoted, laughed at, remembered for years — are actually the product of one of the most corrupt institutions in American agriculture: checkoff programs.

The history of checkoffs is dripping with controversy, greed, and legal challenges. Started as a way for farmers to pool their resources and boost the overall sales of their product, checkoff programs have become a favorite tool for corporate lobbyists seeking to consolidate wealth and power into ever-fewer hands.

Why should the average American care? Well, the checkoff has evolved into a behind-the-scenes machine that extracts money from farmers and ranchers against their will and then funnels it to corporate lobbyists — who work tirelessly to consolidate power over our entire food system into a few hands.

Most of us see only the symptoms — shortages, price hikes, and other newsworthy catastrophes — of the plague of concentrated power wreaking havoc on our health, wealth, and wellbeing.

In this blog, we’ll trace these symptoms back to one of the ailments afflicting today’s food and farm system — and even share how to heal it.

What’s a Checkoff, and What’s It Got to Do with Dinner?

The checkoff is a mandatory fee that many U.S. farmers, ranchers, and producers pay every time they sell any of 22 commodities, including beef, pork, milk, corn, and soybeans.

The fees fund government organizations — called “boards” or “councils” — that do research and promote the product or a commodity as a whole, without mentioning specific brands. Theoretically, the producers benefit from the research, product development, consumer education, and promotional activities they are all collectively funding. So a promotional campaign like “Got Milk” was intended to boost awareness about milk, increasing demand and profits for everyone in the dairy industry.

The trouble is, these councils take money from every producer, but they don’t benefit every producer — and in fact do demonstrable harm to some. We’ll get into that issue later.

How Did Checkoff Programs Come to Be?

Checkoff programs were originally voluntary — they got their name because farmers had to literally check off a box to pay into the shared promotional and research fund. Eventually, Congress provided the authority for boards to require mandatory fees from producers.

This makes checkoffs essentially a tax that farmers must pay on their production of goods. Nationwide, checkoff programs collect about $900 million from America’s farmers and ranchers every year.

The government’s official name for checkoffs is “Research and Promotion Programs,” and the USDA’s Agricultural Marketing service is tasked with oversight for the use of their funds. The rules include things like prohibitions against lobbying for policies — keep reading to judge for yourself how closely that rule is followed.

Who or What Is Behind Catchy Slogans Like “Beef. It’s What’s For Dinner?”

Let’s pull the curtain back on a few of these programs. What are the names of the groups in charge of each checkoff program? How much money do they collect from farmers? And who do they give it to?

The National Dairy Promotion and Research Board is the government body that manages the federal checkoff program. Farmers fork over 15 cents per 100 pounds of milk sold, which ends up being about $35 per cow, per year. The Board’s annual checkoff revenues were $364 million in 2021, making dairy the biggest checkoff by far.

The Dairy Board then contracts with Dairy Management, Inc. (DMI), a lobbying organization, handing over $110 million in checkoff dollars in 2021. DMI uses that money taken from America’s struggling dairy farmers and splurges on high-profile corporate partnerships: $5.8 million to Domino’s and $6 million to the NFL, among others. These splashy campaigns do nothing to help the farmers funding them.

Meanwhile, the U.S. lost 20,000 dairy farms between 2010 – 2020.

At the federal level, the Cattlemen’s Beef Board (CBB) manages the government checkoff program, joined at the state level by several beef councils. Cattle ranchers are forced to pay $1 per head of cattle every time the animal is sold; more than $1 billion in checkoff fees have been collected since the Beef Promotion and Research Act created the beef checkoff program in 1985. Ranchers paid 70 million in 2021, of which $43 million went to the CBB.

CBB and state beef councils turn right around and hand the lion’s share of those dollars to the National Cattlemen’s Beef Association (NCBA), a lobbying organization representing corporate meatpacking conglomerates like Tyson, Cargill, and National Beef. Checkoff funds comprise more than 70% of NCBA’s budget; in 2020, their total checkoff fund revenue was $45,647,670.

Meanwhile, the U.S. lost a half a million cattle producers between 1980 – 2017.

The National Pork Board (“Pork Board”) manages the government-mandated checkoff program. Farmers shell out 40 cents for every $100 of pork sold; in 2021, the Pork Board collected more than $94 million in checkoff fees from America’s pig farmers.

The Pork Board has an unusually close operational relationship with the National Pork Producers Council (NPPC), a lobbying group that counts Cargill and Purina among its members. The Pork Board pays NPPC for things like rental fees for its headquarters, and until recently, the Pork Board paid NPPC millions every year to license the defunct slogan “Pork. The Other White Meat.” Despite the activities of the Pork Board and NPPC, pork consumption in the U.S. fluctuates, dropping to record-low levels in 2012 and 2014.

Meanwhile, the U.S. has lost more than 70% of our pig farms just since 1990.

NPB pays NPPC for things like rental fees for its headquarters, and until recently, NPB paid NPPC millions every year to license the defunct slogan “Pork. The Other White Meat.” Despite the activities of NPB and NPPC, pork consumption in the U.S. fluctuates, dropping to record-low levels in 2012 and 2014.

Meanwhile, the U.S. has lost more than 70% of our pig farms just since 1990.

Dairy

The National Dairy Promotion and Research Board is the government body that manages the federal checkoff program. Farmers fork over 15 cents per 100 pounds of milk sold, which ends up being about $35 per cow, per year. The Board’s annual checkoff revenues were $231 million in 2021, making dairy the biggest checkoff by far.

The Dairy Board then contracts with Dairy Management, Inc. (DMI), a lobbying organization, and provides it with about $160 million a year in checkoff dollars.

DMI uses that money taken from America’s struggling dairy farmers and splurges on high-profile corporate partnerships: $5.8 million to Domino’s and $6 million to the NFL, among others. These splashy campaigns do nothing to help the farmers funding them.

Meanwhile, the U.S. lost 20,000 dairy farms between 2010 – 2020.The Dairy Board then contracts with Dairy Management, Inc. (DMI), a lobbying organization, and provides it with about $160 million a year in checkoff dollars.

Beef

At the federal level, the Cattlemen’s Beef Board (CBB) manages the government checkoff program, joined at the state level by several beef councils.

Cattle ranchers are forced to pay $1 per head of cattle every time the animal is sold; more than $1 billion in checkoff fees have been collected since the Beef Promotion and Research Act stood up the beef checkoff program in 1985.

CBB turns right around and hands the lion’s share of those dollars to the National Cattlemen’s Beef Association (NCBA), a lobbying organization representing corporate meatpacking conglomerates like Tyson, Cargill, and National Beef are among the members. Checkoff funds comprise more than 70% of NCBA’s budget; in 2020, their total checkoff fund revenue was $45,647,670.

Meanwhile, the U.S. lost a half a million cattle producers between 1980 – 2017.

Pork

The National Pork Board (NPB, or “Pork Board”) manages the government-mandated checkoff program. Farmers shell out 40 cents for every $100 of pork sold; in 2021, the NPB collected $100 million in checkoff fees from America’s pig farmers.

The Pork Board has an unusually close operational relationship with the National Pork Producers Council (NPPC), a lobbying group that counts Cargill and Purina among its members.

These numbers demonstrate that checkoffs have become nothing but a pipeline siphoning money from farmers to fund corporate lobbying efforts — despite the rules against that very activity.

Bill Bullard, CEO of the independent cattle ranchers’ organization R-CALF USA, put it this way: “Without the checkoff dollars, you wouldn’t have the NCBA in its current form, so it’s ridiculous to take at face value that this lobbying firewall really works.”

The checkoffs’ government mandate lends a mask of credibility to these lobbying groups, making it appear that they speak on behalf of producers — even as they put them out of business.

What Controversies Have Checkoff Programs Stirred up?

Collusive Relationships

Over time, the checkoff boards tasked with research and promotion have gotten awfully, illegally close to the lobbying organizations in their sector that influence legislation and government action — despite a broad statutory prohibition against these activities.

The dairy checkoff organization, the National Dairy Promotion and Research Board, and the trade lobbying group, Dairy Management Inc. have an extremely close relationship. Until Sept 2021, Tom Gallagher was the CEO of both. His combined compensation from both roles was $1,512,930 — all as the farmers who pay this salary go out of business.

Then there’s the case of the National Pork Board, the checkoff organization, which has joined forces with the pork lobby, the National Pork Producers Council (NPPC). NPPC recently called the Pork Board its “sister organization” — despite the fact that NPPC is a lobbying organization and the Pork Board is supposed to be policy-neutral. NPPC and the Pork Board hold joint annual meetings, which demonstrate and symbolize the Pork Board’s support of NPPC’s policy agenda. They also jointly operate the “We Care” industry PR program — which serves as NPPC’s primary public messaging venue.

The close relationship between these two has been raising red flags as far back as 1999, when an Inspector General report called on the government to separate the operations and interests of the lobbying group and the checkoff board.

Lack of Transparency

The murky workings of checkoff programs have been a thorn in the sides of farmers, advocates, and government oversight agencies for years. The Paper and Packaging checkoff program kicks the public out of its supposedly public meetings after roll call. The dairy checkoff, being the largest pool of money, is legally required by Congress to submit annual financial reports — but failed to do so for five years.

Everybody Pays, but Not Everybody Benefits

Promotions funded by checkoff programs are not allowed to distinguish between different production types, such as grassfed or regeneratively raised cattle.

By reinforcing the idea that all beef is equal, these advertisements disadvantage premium beef products — even as producers are forced to help pay for them.

Misuse of Funds

This is a big one. When you start looking for it, you find that inappropriate use of farmers’ and ranchers’ hard-earned dollars runs rampant among these government programs.

We can find several examples of this in the beef sector alone. In 2010, an independent audit examining the equivalent of just nine days of beef checkoff program spending found that the primary beef checkoff contractor, the National Cattlemen’s Beef Association (NCBA), had improperly spent more than $200,000 in checkoff funds on lobbying and overseas vacations. Despite a Freedom of Information Act complaint, the full audit has not been released to the public.

On the state level, the Oklahoma Beef Council’s accountant embezzled millions of rancher dollars to open her own clothing boutique. The fact that such brazen theft went on for so long unchecked reveals a staggering lack of oversight.

The American Egg Board went full-on mafia on a plant-based mayo startup, hiring a PR firm to track the startup’s online presence and tank its online advertising efforts. Egg Board executives exchanged emails about hiring a consultant to pull the product from Whole Foods’ shelves, and even about putting out a hit on its founder. While no one ultimately got hurt, federal investigators determined that the Egg Board’s obsessive campaign focusing on one company and product — and failure to submit the budgets for that campaign to the USDA for review — violated federal guidelines. The criticism of the Board’s inappropriate behavior and ensuing public fallout sent its Chief Executive Joanne Ivy into early retirement.

The National Pork Board (the checkoff program) continued to pay the National Pork Producers Council (the lobbying group representing industrial pork production) $3 million per year for the “Pork. The Other White Meat” slogan for years after it was defunct in a murky licensing scheme. Independent pig farmers sued on the basis that their checkoff dollars shouldn’t go to NPPC, which actively worked against their interests.

The corruption isn’t limited to meat and protein checkoffs, either. A truly scandalous complaint filed by soybean growers accused the United Soybean Board of a number of serious crimes: theft, sexual harassment, and even assault by then-CEO of the U.S. Soybean Export Council.

An investigation by the Office of Inspector General followed, and in 2010 revealed that the Export Council had also doled out more than $300,000 of growers’ checkoff dollars to its staff as “bonuses.”

Why Hasn’t the Government Done Something About These Repeated Violations?

The USDA’s oversight of checkoffs has been notoriously lax, allowing for the full corporate seizure of these programs.

A 2014 report from the Office of the Inspector General found that the Agricultural Marketing Service “needs to strengthen its procedures for providing oversight” of the beef checkoff program. The report also said that the weaker procedures had resulted in “reduced assurance that beef checkoff funds were collected, distributed, and expended” according to the law.

In a November 2017 report, the U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO) found that USDA’s oversight of checkoff programs is insufficient, and called on USDA to increase oversight of the programs. USDA claims to have implemented these changes.

Despite that, and despite these repeated calls for increased transparency and accountability, farmers have yet to see any real, lasting improvements to checkoff programs.

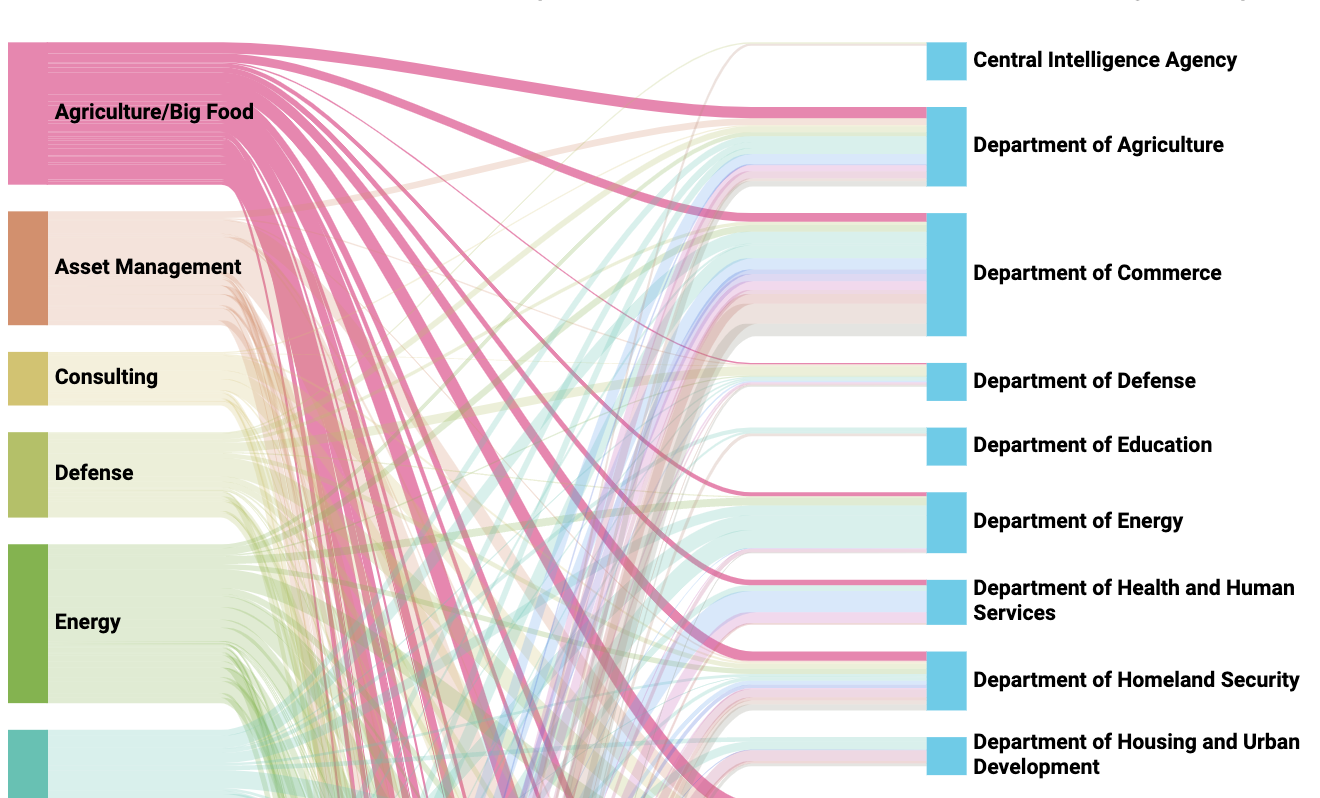

This may be in part because the revolving door between the USDA, checkoff programs, and dominant corporations sees a lot of traffic.

One very high-profile person has swung through that door and back at least a couple of times: from 2009 – 2017, Tom Vilsack was Secretary of Agriculture. At the end of the Obama administration, Mr. Vilsack landed the highest-paid position at the nation’s largest checkoff program — CEO of the U.S. Dairy Export Council — only to become USDA Secretary again in early 2021.

Mr. Vilsack is just one of many former representatives of Big Ag in government positions with regulatory and enforcement authority. Given such deep and numerous ties to industry, it certainly calls into question whether any agency could enforce the rules fairly, assertively, and impartially.

What Do Farmers and Ranchers Think of Checkoff Programs?

To put it mildly: not much.

In 2018, the cattle industry magazine Drovers issued a poll asking ranchers if they believed the beef checkoff helped stimulate beef demand and support their cattle business. More than half the respondents said “no,” and the comments section filled with ranchers irate about the mismanaged funds, collusive relationships, and corporate greed they had witnessed with the beef checkoff. Drovers has since removed the poll from their website, but you can still see all of the deleted comments here.

Hog farmers nearly rid themselves of their checkoff once. In 2000, hog farmers successfully petitioned for a referendum on the checkoff. More than 30,000 hog farmers voted in the referendum, and the resulting decision — by five percentage points — was to end the program. But the NPPC challenged the referendum in court. Ultimately, USDA secretary Ann Veneman overturned the referendum result, forcing the hog farmers to continue paying checkoff fees.

The basis for one of the main arguments against checkoff programs is that they violate the First Amendment: by paying a mandatory fee, producers are forced to subsidize speech (promotions and advertisements) with which they do not agree.

This New York Times article documents the legal battles that have used this argument, and explains that it’s most often used by “family farmers or specialty producers who argue that they have nothing to gain, and in fact are harmed, by generic advertising that overwhelms their own efforts to persuade the public that their products are special and worth searching for.”

Ultimately, the Supreme Court of the United States invalidated this argument in 2005 by deciding in a 6-3 vote that checkoff programs are government speech, and are therefore not subject to ordinary First Amendment analysis. Using that same logic, the government has a responsibility to clean it up and ensure it is being deployed fairly.

Who Actually Benefits from Checkoff Programs?

Quick recap: We’ve learned that checkoff programs have a well-documented history of corruption and misuse of funds. We also know that millions collected in checkoff fees are at the full disposal of corporate industry lobbyists — and that government agencies aren’t doing much about it. Finally, we learned that farmers do not benefit from or feel supported by checkoff programs, and that their efficacy at increasing demand is dubious at best.

So in the end, what do checkoff programs actually accomplish? Who is benefitting from their ability to pull dollars from the operations of farmers and ranchers across America?

The answer: If you follow the money, you’ll find it goes from farmers, to the government, and into the hands of lobbyists. Lobbying groups then use these funds to smooth the passage of harmful policies that only enrich a handful of corporations — while damaging the lives and livelihoods of farmers, ranchers, rural Americans, and eaters everywhere.

A few examples:

- A study by the journal Climatic Change revealed the millions spent by dairy and livestock lobbying groups to defeat legislation protecting our environment.

- NCBA has established a vocal and well-funded opposition to the reinstatement of Mandatory Country of Origin Labeling (MCOOL) for beef, which was repealed by Congress in 2015. If MCOOL were reinstated and used exclusively for beef that is born, raised, slaughtered, and processed in the United States, independent ranchers would have a powerful marketing tool that would distinguish their product from lower quality imports sold by JBS or Cargill.

- NCBA was also a strident critic of the Fair Farmer Practices Rules. Also known as the “GIPSA rules,” these were proposed in 2010 as a way for the USDA’s Grain Inspection, Packers and Stockyards Administration (GIPSA) to create a level playing field for independent farmers and ranchers competing against monopolies. NCBA joined other groups representing industrialized monopolies in lobbying hard against these rules; altogether, these agribusiness interests spent $7.79 million in 2010 to successfully lobby against the GIPSA rules.

Via checkoff programs, independent farmers and ranchers are forced to protect and prop up the industrial corporations running them out of business.

What Impact Do These Big Ag-Friendly Policies Have on Everyone Who Eats?

Simply put, checkoff programs are part of a system that rewards the consolidation of power over the food system into a few hands. Checkoffs themselves encourage the production of a commodity — which enriches the corporate industry that controls it — no matter the social, environmental, or long-term economic cost.

Wisconsin dairy farmer Sarah Lloyd told Successful Farming that because checkoffs aim to increase yields regardless of the cost of production, smaller or independent operations like hers lose money on every gallon of milk produced.

And as we’ve learned, a staggering number of independent dairy farms have been forced to close up shop in an economic landscape that heavily favors big, consolidated agribusiness.

By continuing to prop up large corporations with farmers’ money, checkoff programs are exacerbating the cascading effects of consolidation.

In this 85-second video, Sarah Lloyd illustrates this concept vividly: big firms like to work with big farms, raising everyone’s costs along the way and creating an environment in which smaller producers — more likely to be the ones feeding their communities — cannot survive.

Decision-makers have not cared. Former Secretary of Agriculture Sonny Perdue was far from sympathetic to the plight of the dairy farmers who built America’s great dairy industry in the first place: get big or get out, he said in 2019.

Over decades, this attitude has resulted in a highly concentrated food system. These levels of concentration make for a brittle, vulnerable food system that only serves the few corporations that control it.

That means that all of us — farmers and ranchers, rural Americans, food system workers, and everyone who eats — are impacted by the negative consequences of this government-sanctioned pipeline from farmers’ pockets to corrupt institutions.

As eaters, we’re facing higher prices at the grocery store — egg prices are a recent example — and suffering from fake shortages and price hikes when global supply chains are disrupted.

So What Can Be Done about Checkoff Corruption?

Instead of punishing independent producers by forcing them to pay into a system that harms them, we should change the system. Farm Action’s Checkoff Program Reform campaign has identified three primary courses of action.

Make Them Voluntary

To start, a return to a voluntary checkoff would allow farmers, ranchers and producers to opt into checkoff payments as they could when the programs were first envisioned. This gives back power to producers: if the checkoff program is benefiting them, they can show support by opting in. If it is not beneficial, they can voice opposition by keeping their money and putting it to work on their farm or ranch

Reform Them

There is a bill in Congress right now that would restore a great deal of integrity and transparency to these programs. The Opportunities for Fairness in Farming (OFF) Act would:

- Prohibit checkoff programs from contracting with any organization that lobbies on agricultural policy.

- Prohibit employees and agents of the checkoff boards from engaging in activities that may involve a conflict of interest.

- Establish uniform standards for checkoff programs that prohibit anti-competitive activity, unfair or deceptive acts, or any act or practice that may be disparaging to another agricultural commodity or product.

- Require transparency through the publication of checkoff program budgets and expenditures.

- Require periodic audits of compliance with the act by the USDA Inspector General.

Take Action to Reform Corrupt Checkoff Programs

End Them

At the end of the day, we may just need to call it. If checkoffs prove to be beyond repair, they should be eliminated. There is one thing we know for sure: farmers and ranchers should have a say in where their hard-earned money goes.

Written and designed by Dee Laninga; edited by Angela Huffman, Joe Maxwell, and Sarah Carden; concept by Angela Huffman and Joe Maxwell